[18] [18]

Introduction

Arriving in a new country, making new friends and acquaintances, rebuilding social networks that have been lost or left behind, integrating into a new society, learning the social geography of a new city in order to find housing, learn a language or, at the very least, get used to the local dialect, landing a first job in order to secure a measure of financial independence and then trying to improve one's fortunes is, to be sure, both difficult and time-consuming. While all immigrants face these challenges, they do not all experience these difficulties to the same degree.

Those who arrive with an immigrant visa in hand, secure in the knowledge that they are welcome, at least do not have to fear legal uncertainty about their future in their new country, for they have permanent residence from the start. Of course, depending on their personal characteristics (age, gender, education, occupational experience, etc.) and the circumstances of their migration (in part reflected in their admission category: independent, family or refugee), the time it takes them to settle may vary somewhat. [1] But they know that they can settle, that their future is in their new country and they can begin to build new lives as soon as they arrive.

On the other hand, for those who arrive without status, seeking refuge, the process of settlement is likely to be less smooth. They face a period of uncertainty about whether they will be allowed to settle, which will last until they are granted legal landed status; they may not even obtain landed status and be sent back. Moreover, if these individuals applied for asylum for reasons of political uncertainty in their country of origin, or if they experienced physical or psychological abuse, these factors will likely complicate the settlement process; they must not only live with legal uncertainty about their future but must also bear the double psychological burden of adapting to a new society while recovering from physical or psychological trauma.

This study examines these unsure migrants, as refugee claimants must be considered to be. More specifically, it looks at migrants who filed refugee claims in 1997 and were landed in Quebec by March 31, 1997. [2] Only landed refugees were interviewed, both for ethical reasons (it would be in poor taste, to say the least, to ask for the co-operation and trust, for research purposes, of claimants who are likely to be deported), and because they fall fully within the responsibility of the MRCI only once they have the right to settle permanently.

There are consequences, however, to choosing this population; the study does not examine all claimants, only those whose claims were successful. Therefore, the data from this survey cannot be used to assess transition prevalences or probabilities prior to obtaining landing; the study examines only refugees who had positive outcomes, not all those who were liable to experience these transitions.

The analyses presented here are essentially descriptive. Various aspects of the refugee claimants' settlement process will be presented, starting from the filing of the refugee claim.

[19]

After a description of the claimants and the administrative process, their experiences in finding housing, attendance in the school system and the specific courses they took, their experiences with wage employment, and the private and public sources of support they called upon overtime will be presented. The focus, then, will be on the "objective" life experiences of landed refugee claimants in the three years following their refugee claim. A proper exploration of their subjective experiences would demand an entirely different approach from the one adopted here.

Population Under Study and Sample

The study is based on a random sample of 407 respondents aged 18 and over at the time of the claim, taken from a population of 2,034 claimants from 1994 who were landed (obtained the right to establish permanent residence) in Quebec no later than March 31, 1997, and were living in the Greater Montreal area at the time of the survey. A description of this population and a discussion of the sample's representativeness appear in the Appendix. It should be noted here, however, that the sample does not seem biased and that the differences between the sample and the population are likely attributable to a dynamic redefinition of the population. Since claimants' geographic mobility probably increased when they were granted permanent residence, they were able to leave Montreal or Quebec for other parts of Canada; if this is true it would explain the slight overrepresentation of couples, who would be less mobile.

The interviews were face-to-face and took place in the summer of 1997.

Questionnaire

The questionnaire was designed to capture the dynamics of settlement. It included a conventional section and also catalogued the events that respondents experienced from the time they filed their claim for refugee status. Experiences with housing, employment, unemployment and education were all recorded, including beginning and end dates and other particulars. The dates of a number of other events are also indicated, which will help us describe the settlement process overtime. To alleviate the problems of memory entailed by this type of study, given the large number of dates respondents needed to recall, the month has been used as the unit of time in the survey and in the descriptions and analyses that follow. [3]

Preparation of the questionnaire was greatly aided by the experience gained in the study on the settlement of new immigrants (ENI), the work of Christopher McAll and working meetings with a wide variety of individuals interested in the subject. [4]

Time Data

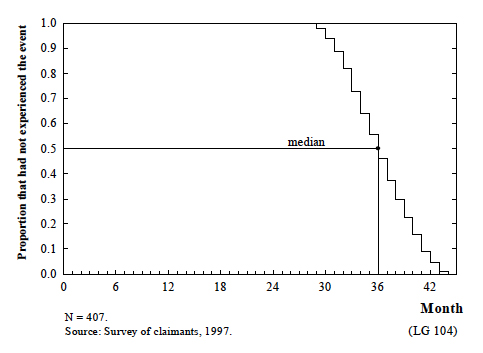

The period under study varied from 29 to 44 months after respondents filed their applications for asylum (Figure 0.1). The median time was 36 months. [5]

[20]

Figure 0.1 – Table of exits from observation (since claim)

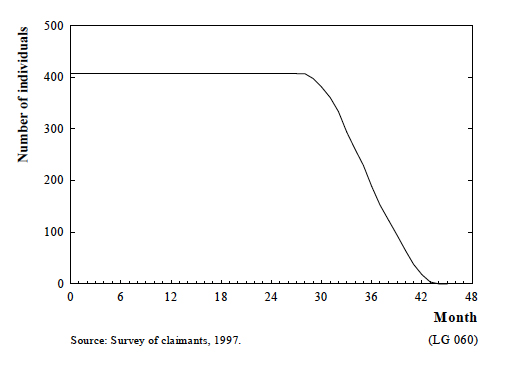

For the first 29 months, the total number of respondents is equal to the total size of the sample (n=407), whereas, after this time, their number decreases. Figure 0.2 shows the size of the sample for every month after the refugee claim. After the 36th month, the total number under study is too small to be robust, especially when the data are broken down using the control variables: gender (Figure 0.3), age (Figure 0.4) and education (Figure 0.5). Our analyses will therefore be limited to this 36-month period.

We will use graphs extensively to illustrate complex data produced by survival tables and time series over 36 months. These graphs and explanations on how to read them appear in the Appendix.

Figure 0.2 – Number of people under observation in each month

[21]

Figure 0.3 – Number of people under observation in each month, by gender

Figure 0.4 – Number of people under observation in each month, by age group

Figure 0.5 – Number of people under observation in each month, by education level

[1] For a description of immigrants who have this status upon arrival, see Jean Renaud, Alain Carpentier, Catherine Montgomery and Gisele Ouimet, La première annee d'établissement d'immigrants admis au Quebec en 1989. Portraits d'un processus (Montreal: Ministère des Communautes culturelles et de l'lmmigration, 1992), 77 pp., and Jean Renaud, Serge Desrosiers and Alain Carpentier, Trois années d'établissment d'immigrants admis au Québec en 1989. Portraits d'un processus, Études et recherches No. 5 (Montreal: Ministère des Communautés culturelles et de l'lmmigration, 1993), 120 pp.

[2] According to MRCI figures, between 1989 and 1994, about half those defined as claimants were granted permanent residence. Thus, many claimants obtain permanent residence in the first three years. For more on this, see the note on methodology in the Appendix by A. Carpentier and G. Pinsonneault, Refugee claimants from 1989 to 1994 : general description and assessment of representativeness of a 1994 sample of landed claimants. The study on 1994 claimants who were granted landed status by the summer of 1997 therefore gives a picture of the most recent nearly-complete cohort.

[3] For more on this, see Jean Renaud, Alain Carpentier, "Datation des évenèments dans un questionnaire et gestion de la base de données," in A. Turmal, ed., Chantiers sociologiques et anthropologiques. Actes du colloque de I'Acsalf, 1990 (Montreal: Meridien, 1993), pp. 231-260.

[4] Christopher McAll, Louise Tremblay. Les requérants du statut de refugié au Quebec : un nouvel espace de marginalité ? Études et recherches No. 16 (Montreal: Mnistère des Relations avec les citoyens et de l'lmmigration, 1996), 142 pp.

[5] The terms "median duration" and "median time" are often used in this report. They refer to the middle value dividing the sample in two. In this case, median time refers to the duration of the survey for 50% of the sample.

|