|

[235]

Joëlle Robert-Lamblin [1]

Anthropologue, Docteur d’État ès Lettres,

Directeur de recherche de classe exceptionnelle honoraire depuis 2008

(CNRS, France)

“Demographic Fluctuations and Settlement Patterns

of the East Greenlandic Population

- as Gathered from Early Administrative

and Ethnographic Sources.”

Un texte publié dans l’ouvrage sous la direction de Jette Arneborg & Bjarne Gronnow, Dynamics of Northern Societies. Proceedings of the SILA/NABO Conference on Arctic and North Atlantic Archaeology, Copenhagen, May 10th-14th, 2004, pp. 235-246. SILA-The Greenland Research Centre at the National Museum of Denmark. Publication from the National Museum, Studies in Archaeology & History Vol. 10, Copenhagen 2006.

- Introduction [235]

-

- History and environmental context [236]

- Dynamics of a small-scale society : factors regulating group size [236]

- Demographic mechanisms [236]

- "Normal" mortality, given living conditions and environment [237]

-

- More exceptional causes of death [237]

- - Starvation [237]

- - Homicides [238]

- - Accidents occurring during moves [238]

- - Epidemics [238]

-

- Female fertility and birth rate [238]

- Socio-cultural responses [239]

- Mobility and territorial occupation strategies [240]

- - Distant migrations [242]

- - Migrations within the ethnic "borders" [242]

- Other forms of social adaptation [243]

- - Polygamy [243]

- - Adoption [244]

-

- Conclusion : Various customs and survival techniques [244]

- References [245]

-

- Notes [246]

[235]

Introduction

Small human groups comprising few individuals are subject to wide demographic variations. These very pronounced movements can lead them to total extinction or, conversely, to demographic expansion causing them to spread into new territories.

The history of Arctic hunter-gatherers presents a range of examples that are likely to be of use to archaeologists and prehistorians as a complement to their field research. For instance, when numerous ruined habitats dating from the same period are present, it is difficult to know whether this was simultaneous habitat reflecting relatively a high population density or, conversely, whether it was occupied sporadically by a small population that had to be continually mobile in order to maximize captures from hunting. Similarly, before concluding from the small number of burials brought to light that the population density of a region was low, the situation has to be considered from the angle of different possible burial customs. Some may involve leaving bodies to be devoured by wild animals, so that the dead might come back to life through these animals (as with the Chukchis). Others consist in cutting up bodies of enemies into pieces to be thrown away and dispersed, so that they cannot return for revenge, or in throwing the dead into the sea to allow them to reach the best possible world beyond (as with the Ammassalimiit). Customs such as these do not leave any archaeological traces. The same goes for accidental deaths in kayaks or umiaq, or as a result of ice breaking up during sledge journeys.

This paper analyses the factors involved in the dynamics of small hunting communities, drawing on research on the population of Eastern Greenland and its various social and cultural responses to specific situations. The main interest of the example presented here lies in the exceptional wealth of information concerning the historic, demographic and socio-economic evolution of population in question since it was first "discovered" by Westerners. A first nominative census of the Ammassalik population was drawn up during the winter of 1884-85 by Johannes Hansen, also known as Hansêrak (Hansen 1911), who accompanied the Danish discoverer Gustav Holm (Holm 1887,1911). Another census followed in 1892, during a short visit by C. Ryder (Ryder 1895). Thereafter, others were drawn up each year as from 1895, by administrators of the new colony (Johan Petersen, then A. T. Hedegaard). Parish registers exist for those baptised since 1899 (Christian Rosing).

Hansêrak and Holm had estimated the ages of the people they met in 1884, based on two specific events which can be dated : the voyage of Graah to south-east Greenland in 1830, and the passage of the comet Donati in 1858. Although there may be some errors in the ages estimated for the oldest individuals and some omissions among very young children, this "snapshot" provided by the very first census of 1884 provides a mine of unique information on a hunter-gatherer society that had never had any direct contact with the Western world. Later documents enabled us to correct some errors and fill in some gaps. These early administrative archives also provide a mass of data on habitat, equipment, means of transport etc. Bringing together all this very precise information makes it [236] possible to use an approach to social phenomena that is not purely descriptive, but also quantitative and measurable.

History and environmental context

The Ammassalik region is located on the eastern coast of Greenland, just below the Arctic Circle, where the very harsh climate creates extreme living conditions. For the period 1884-1902, the annual mean temperature was -2° ; for the coldest month (February) the average was -11° and +6° for the warmest month (July). The ground is covered with snow for about 260 days a year and the ice pack, which can be over 100 km wide, prevents access to this region for nine or ten months of the year. This accounts for the extreme remoteness of this territory and the very late discovery of the Ammassalik population.

There is little life on the narrow coastal fringe between the ice pack and the Inland Ice (Indlandsisen). There are few species of fauna and few individuals (foxes, polar hares, ptarmigans), while the meagre tundra vegetation is inaccessible for most of the year due to the long period of snow cover. The marine world -mammals, fish, molluscs, crustaceans and seaweed, not to mention precious driftwood - furnished the basic essentials for the survival and material culture of the Ammassalimiit.

Like other indigenous Arctic populations, the inhabitants of the eastern coast of Greenland have adapted their technology and their social structure to the resources available from their environment. But these resources have been altered on the one hand by climatic variations and on the other hand by overexploitation by external populations, such as intensive whale hunting by Europeans along the ice pack rim. The whales having disappeared from their coasts in the early 19th century, seals became the mainstay of the East Greenlanders' livelihood. With this major ecological change, men had to disperse to hunt more individually, which resulted in a smaller ratio of consumers to producers.

The general history of Eskimo/lnuit populations thus reflects climatic fluctuations leading in turn to fluctuations in the fauna, with repercussions on human populations : some small groups were able to adapt and eventually to conquer the Arctic environment, while others became extinct. A case in point concerned a small group of a dozen individuals, including women and children, who, on being met by Clavering in North East Greenland in August 1823, disappeared in fright when shots were fired and were never seen again.

The main historical landmarks during the period of the first contacts in Ammassalik are :

- - 1884 : the Dane Gustav Holm discovers the population ;

- - 1894 : beginning of colonization ;

- - 1899 : first baptisms, followed in 1900 by the first religious marriages ;

- - 1905 : presence of the first East Greenlandic midwife, and a second in 1910 (West Greenlandic) ;

- - 1915 : introduction of the seal net for winter hunting ;

- - 1921 : Christianisation completed ;

- - 1925 : establishment of the Scoresbysund colony, with emigration of 10% of the population.

Dynamics of a small-scale society :

factors regulating group size

In such an environment, how did the Ammassalik ethnic group cope with temporary or more fundamental imbalances ? Studies of the period before and after the first contacts with Westerners have helped to gain a better understanding of the processes at work.

- Demographic mechanisms

Before the introduction of sanitary amenities of any kind, the demography of this group of Arctic hunters was characterized by high mortality and a high birth rate. Reconstituted genealogies and the data we collected show that at the end of the 19th century, death and birth rates were between 30 and 40%. Periods of severe demographic contraction due to crises or catastrophes (starvation, collective accidents) were followed by periods of robust recovery as soon as living conditions improved. Life expectancy was below 40 years for both sexes and lower for men than for women. Few individuals reached or lived beyond the age of 55 (only 4% in the first census in 1884).

[237]

- "Normal" mortality, given living conditions and environment

In the very harsh environment of East Greenland, the periods with the greatest risk of death among individuals were first of all at birth and during the first week of life, and then during the full exercise of adult activities, from 17-20 to 45-48 years of age, when men spent most of their time hunting and women gave birth to their children (Robert-Lamblin et Masset 1999).

- - in 1896-1906, 7 women died in childbirth (for 226 births), while 9 men died in kayaks

- - in 1907-1916, 8 women died in childbirth (for 273 births), while 7 men died in kayaks

As well as a high death rate among women during childbirth, there was over-mortality among men due to hunting accidents (numerous deaths in kayaks) as well as to violent deaths (homicides and blood feuds), to which we will return below.

Infant mortality was very high [2], particularly among newborns on delivery and during the few hours that followed. There were no midwives as such in the traditional society ; women gave birth alone or were helped by an old woman in the family group. During delivery, the total lack of hygiene for both mother and child caused high mortality among both. The presence of one, and later several midwives trained in Western Greenland or Denmark eventually helped to reduce perinatal mortality at the beginning of the 20th century.

More exceptional causes of death

- - Starvation

Several periods of famine are mentioned in accounts made by early observers. Some occurred before the arrival of Holm, and others later on.

Before the arrival of Holm, entire households were wiped out during the two winters of 1881 and 82. This was a succession of two particularly cold winters, separated by a bad summer when the ice remained too thick and did not melt, so that the population could not collect the provisions they needed. An estimated 70 individuals died during these famines (Mikkelsen 1934 : 46). Details are as follows [3] :

- in Nunakitseq in 1881-82 : at least 15 people died of hunger ; only one woman survived ;

- In Qernerti(e)vartivit in 1881-82 : in a household of 19 people, 15 people died of hunger (13 of them were eaten by survivors) ; only two women survived and two adult men had left to look for help or escape the famine ;

- at Akinnaatsiaat in 1881-82 : several deaths ; only two women survived ;

- at lissalik, at least six deaths in 1882-83 : some of the dead were eaten by the survivors ;

- in the north, three umiaq left for Kialineq in 1882 : there was starvation and necrophagia and all the migrants died (some 40 individuals) ; one of the umiaq had come back to Sermiligaaq but went back north.

After Holm's departure, episodes of famine continued to occur in Ammassalik and in the south :

- in Ammassalik fjord, during the winter of 1885-86 ;

- between 1885 and 1891, five people died of diseases caused by the famine ;

- towards 1891, among families migrating south, nearly half of the 57 people travelling in three umiaq died of hunger during a forced overwintering in Anoritee(oo)q (south of Skjoldungen), as well as the passengers of another umiaq, which had separated from the group to go its own way ;

- again, in 1892-93, a very hard winter. At Qinngeq, 6 people died (3 adults and 3 children) ; women and orphans were abandoned ; older people chose to kill themselves by jumping into the sea ; one father ate his children ;

- in 1894-95, during a bad hunting season in Sermiligaaq, the people had to kill and eat their dogs to survive ;

- starvation in February 1897, with some inhabitants ending up eating skins and old boot soles ;

- in 1906 and 1907, bad winters in Kulusuk : famine, dogs eaten ; and yet local administrators gave no help and no food was distributed ;

- in 1908-1909, the dogs were eaten, and in the spring of 1908, many infants died of malnutrition.

From 1915, when seal nets to be set under the ice were introduced in Ammassalik and widely adopted, seal catches in the winter became more [238] abundant. "The seal net saved our lives", an old man from Ammassalik told me, "before, when the snow was too thick, we died of hunger".

- - Homicides

Despite the existence of a remarkable institution, that of contests which involved singing to drumbeats, and which were organised to channel the violence of conflicts and avoid risks of revenge, 14 murders of adult men occurred between 1886 and 1896, representing nearly 18% of the active male population aged 15-54 (Robert-Lamblin 1997 : 264). These deaths were even more dramatic in view of the fact that the disappearance of one adult male would also cause the death of his wife and children who were left without a provider of game. Originally these murders were due to rivalries between hunters or shamans, jealousy over women, or to the absolute obligation for a man to avenge a murdered parent, creating family vendettas of the blood feud type where murder would always be answered by murder.

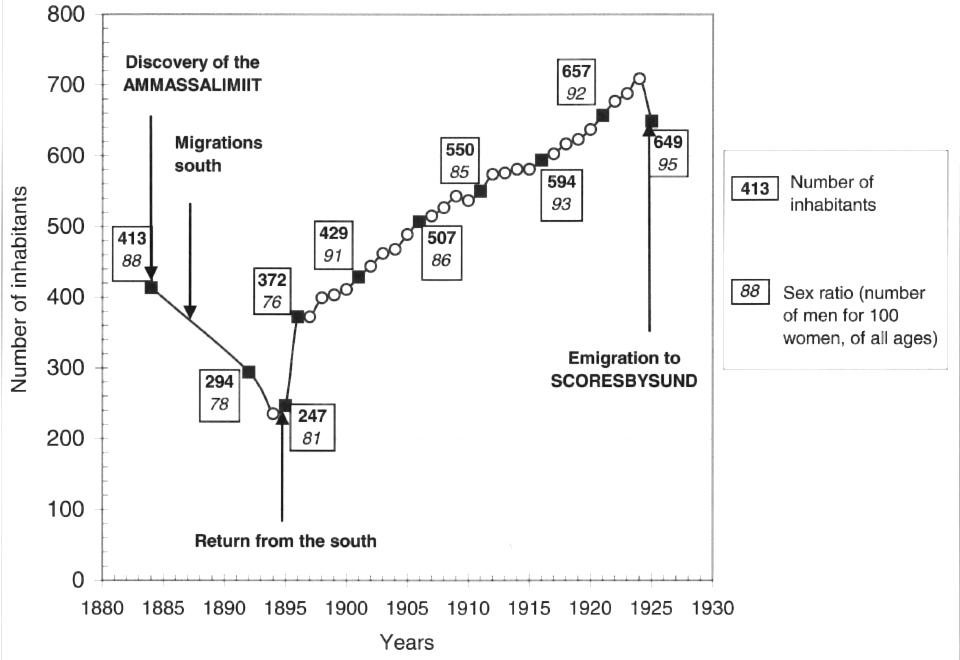

Fig. 1. Birth and death rates among the Ammassalik population

during the first years of colonization.

* in 1897, epidemics among infants ; 1898, common cold ; 1900, common cold. ** in 1903, common cold ; 1904, numerous stillbirths.

*** in 1908, malnutrition among infants ; 1910, whooping cough and influenza. **** in 1914-15, influenza and chicken-pox ; 1918, common cold and pneumonia.

- - Accidents occurring during moves

In this environment, moving from place to place involved numerous risks. In winter or spring, the ice could break up under the weight of a person or a sledge. But the dangers were greater in open water when an umiaq full of women and children could capsize, as for example when an iceberg exploded or overturned. According to P.-E. Victor, an umiaq owned by Nadanieli Kuninge capsized on July 30th 1914, carrying 13 people. The only survivors were the owner and a baby boy of 11 months. Such accidents would not have been rare.

- - Epidemics

The very remote life of the Ammassalimiit made them very vulnerable to contagious infectious diseases carried by Westerners, for which they had no immune defences. Even simple colds could trigger deadly epidemics (Fig. 1).

Female fertility and birth rate

Contrary to what had been written by some authors such as Rink, Dalager, Glahn, Cranz or Nansen on the low fertility of Eskimo women [a statement that the physician A. Bertelsen has strongly opposed, citing the case of women from the area of Uummann(a)aq (Bertelsen 1907)], the women of Ammassalik were very fertile. R. Gessain gives a figure of 7.7 children per woman aged 20-44, in 1935 (Gessain 1973 :1). Infant mortality was very high, as we have seen, and only 3 or4 children survived out of the 8 or 9 a woman might have given birth to. The intervals between births were linked to lengthy breastfeeding, varying from 24 to 36 months, but could also be considerably shortened if the infant died and lactation ceased. The birth rates given in Figure 1 and the population increase shown in Figure 2 speak for themselves and confirm a strong reproductive trend among the women of Ammassalik.

[239]

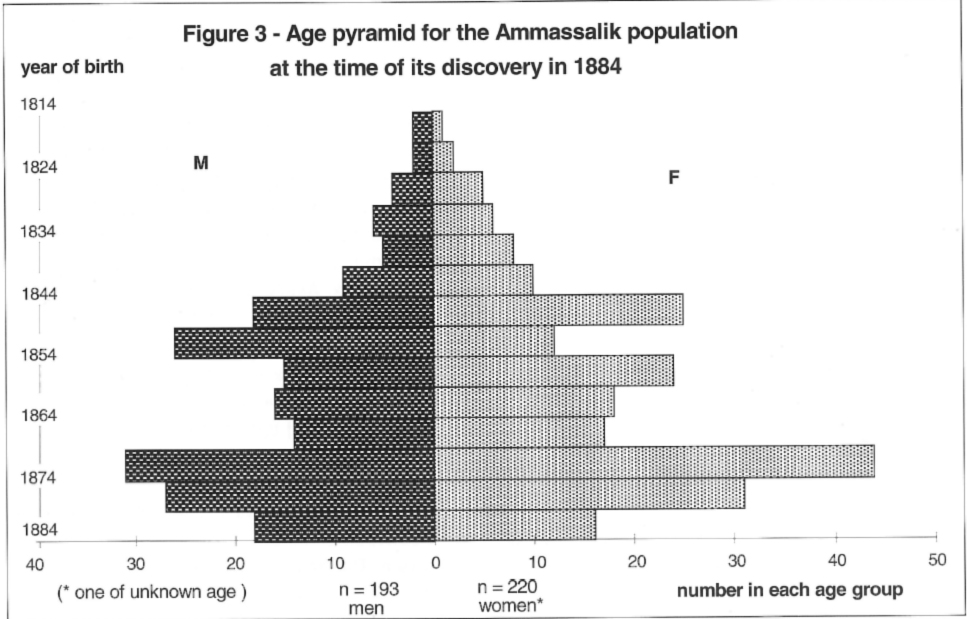

Figure 2 - Evolution of the Ammassalik population

from 1884 to 1925 and evolution of the sex ratio

However, the shape of the age pyramid for 1884 (Fig. 3), which is narrow at the base (for ages 0-4), can be explained by the heavy tribute paid to famine during the two preceding winters. Starvation appears to have particularly affected young children suffering from malnutrition due to the impoverishment of their mother's milk, while the lack of fresh food affected the entire population. Under-nutrition would also have temporarily affected the women's fertility. Finally, it is also likely that some children were forgotten while establishing this first census.

The Ammassalik ethnic group thus follows the typical demographic pattern of small-scale nomadic groups of hunter-gatherers, which are subject to alternating periods of expansion and high mortality. As emphasised by I. Krupnik (1993 : 50, 226), these processes are one of their adaptations to the environment.

Socio-cultural responses

Among these, geographical mobility and some specific social practices need particular mention. The habitat of this ethnic group is essentially contained within the shores and islets of three great fjords : Sermilik, Ammassalik (the most populated) and Sermiligaaq. Traditionally, their habitat was widely dispersed over the territory, with only one house per site. However, although households generally lived in isolation during the winter so as to maximize hunting opportunities through the long, hard cold season, most of the time a relative proximity to another household was sought so that help could be found in case of need. Sharing of food between all inhabitants of a house was a strict rule. The age pyramid for 1884 shows that there were 86 active hunters (men aged 20-55) for 413 people. Thus, one man had to feed around 5 [240] individuals, as all men were necessarily hunters even though they may not have been equally competent.

At this time, the population was distributed among 13 wintering sites, each consisting of one communal house built of stones and earth. The most populated settlement included 14% of the entire ethnic group (Ikkatteq, with 58 inhabitants) and the least populated had 3% (Akernernaq, with 12 inhabitants). The average was therefore of 32 inhabitants in each large patriarchal dwelling occupied during the long period of cold and darkness, from August or September to April or May. However, during the summer, between May and September, this large family unit would split into smaller groups or nuclear families, to live under a tent as very mobile nomads. The 37 sealskin tents recorded in the census at the time of their discovery housed about 11 people each. It was during the period of light and warmth that the various seasonal food resources were gathered (fish, migrating birds, bird's eggs, herbs and berries, large migrating seals) and provisions made for winter.

- Mobility and territorial occupation strategies

Great geographical mobility was characteristic of the Ammassalik population, and their material culture was adapted to this, whether in their modes of transport (umiaq, kayak and dog sled) or in the implements they used in daily life. We will not deal here with seasonal migrations, although they are an integral part of Eskimo culture, so well described by Marcel Mauss in his "Essai" (1906), but will look more specifically at winter migrations. As an essential element in the life of these hunters, mobility was facilitated by several factors :

- very few personal belongings ;

- the self-sufficiency of family groups ;

- absence of activities requiring specialization (except for those of the shamans) : all individuals were practically interchangeable according to sex and age ;

- the very high quality of the means of transport for migration, and more particularly of the umiaq, a collective craft allowing whole families to move with their possessions and dogs.

[241]

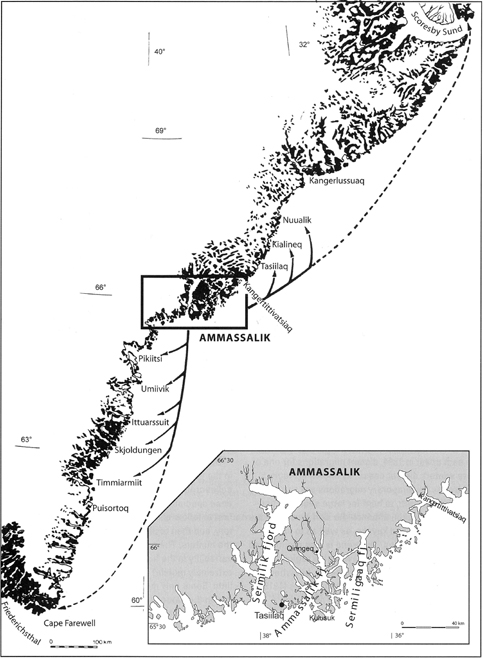

Fig. 4. Map showing the Ammassalik area and the distant migrations

of the Ammassalik population along the Eastern coast of Greenland.

[242]

We have made a distinction between distant migrations beyond the Ammassalimiit territorial limits, and migration within their territory (Fig. 4) :

- - Distant migrations

These could be motivated by :

- a decision to seek out new or specific resources : rare game, raw materials (such as wood, soap stone, bone, ivory) or a desire to barter with the southeastern Inuit tribe or even with foreigners in the south ;

- the need to respond to geographical expansion by exploiting new territories ;

- the need to manage violence : avoidance of strong tensions, flight from a doomed site, leaving for distant areas through fear of vengeance or evil magic, for example.

These were major moves involving several umiaq and kayaks, as in the case of the families met by Holm in 1884 near Umiivik. They had left for the south in 1882 in order to do barter (42 people in three umiaq and 10 kayaks), while at the same date three umiaq had gone north towards Kialineq or Nuualik with some 40 people (Holm 1887 : 56 ; Thalbitzer 1914 : 345-46). Later on, between Holm's departure (1885) and Ryder's arrival (1892), perhaps in 1891 according to Thalbitzer (1914 : 348), 7 umiaq coming from the area of Ammassalik went south, with 114 people, 82 of whom settled in Umiivik and 32 further south [4].

Even after the establishment of a trading post on the east coast in 1894, distant migrations for one or more winters did not cease, as shown in Figure 5. The trends for temporary migrations are strong towards the south, to hunt for large seals, particularly bearded seals, of which the skin is used as the cover for umiaq and kayaks, as well as to make straps and boot soles. The trend is less pronounced towards the north, a more favourable region for hunting narwhals, walruses or bears, but where the climate is noticeably colder. In some years (1919 and 1921), migrants accounted for more than a quarter of the Ammassalik population, which reflects the high degree of mobility among the majority of this ethnic group. Even as the number of houses built increased in Tasiilaq, Kulusuk and Kuummiit, the other wintering sites still consisted of only one dwelling.

The establishment of a community in Scoresbysund (now Ittoqqortoormiit) in 1925, when 70 Ammassilimiit left for the north, represented a new type of migration. Volunteer families were transported by steamer ship and established in houses built especially for them. Contrary to what they believed, they would never return to their native region.

- - Migrations within the ethnic "borders"

As we have already mentioned, the reason for these migrations was the need to optimise hunting territories without exhausting the environmental resources of the area. The decision as to the location of a wintering site was taken in the autumn by the head of the family, an experienced hunter having authority in such matters over his whole family clan. He would decide on the site and on the persons who would live in it for the whole winter period. His choice was mainly guided by the need for a location that was both accessible and rich in game. Often, the family group thus formed moved into the ruins of a pre-existing house, which they rebuilt, adapting its size to their needs (Mobjerg and Robert-Lamblin 1990). Although territorial property rights do not exist here as such, we do find, in the patterns of occupation of the shorelines, ancient family customs that are akin to a customary right of use covering certain geographical areas. These reveal social sub-divisions within the ethnic group, overlaying a geographical division into three zones.

Our computer analysis of this population's moves in the years following their discovery, carried out in collaboration with the Icelandic behavioural science specialist Magnus S. Magnusson, enabled us first to follow all the group's moves within its territory, and then to identify the individual behaviour of the hunters. The analysis showed wide individual variability in the hunters' moves. Some were extremely mobile [5]. Others, however, moved very little. Some only moved within the same region, i.e. within the same fjord system that determines the ethnic sub-groups ; others moved to different fjords or further north or south of Ammassalik. Very mobile individuals are of particular interest because they must have played an important part in the transmission of information concerning the environment, the physical characteristics of different [243] localities (microclimate, resources, accessibility) and possibilities for living there as family communities. Moreover, they would also spread knowledge held by those they would meet. These men are probably an archetype of those who led the way in the conquest of the Arctic coasts, bringing others in their wake.

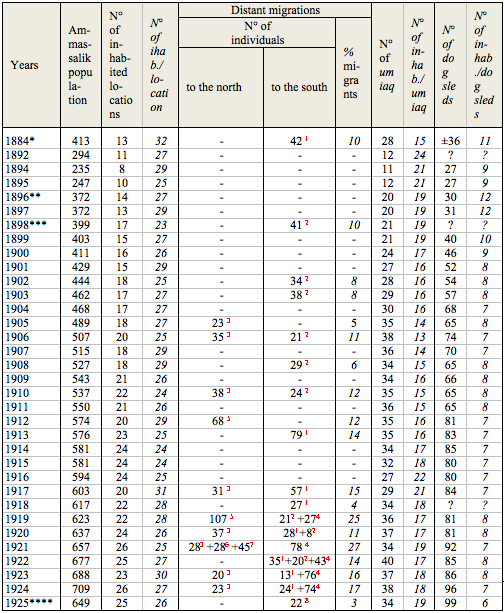

Fig. 5. Evolution of the East-Greenlandic population between 1884 and 1925.

Number of inhabitants, inhabited locations, umiaq and dog sledges.

* after 1884, emigration of 114 individuals southward.

** 1896, return of 118 individuals.

*** 1898, return of 19 individuals

**** 1925, emigration of 70 individuals to Scoresby Sund

Distant winter sites : l Umiivik ; 2 Pikiitsi ;3 Kangertittivatsiaq ; 4 Ittuarssuit ;

5 Kialineq ; 6 Tasiilaq ; 7 Nuualik ; 8 Timmiarmiit

Sources : - Danish archives : G. Holm, C. Ryder, A. Hedegaard, J. Petersen

- French archives : R. Gessain, P.-E. Victor, J. Robert-Lamblin

- Other forms of social adaptation

- - Polygamy

In view of male over-mortality and the permanent imbalance of the gender ratio, i.e. the number of men per 100 women (Fig. 2) in this small group with a restricted number of members, the presence of two wives (or very rarely three) for one hunter was a solution [244] to partially absorb the surplus of adult women who were deprived of economic support. The age difference between co-wives could vary from 3to 20 years, the general pattern being that once the first wife had gained experience in daily chores and activities, a younger one would be brought in to help her and to ensure the continuity of descent. The following can be established from the censuses :

NB : Some of these "widows" or "divorcees" were undoubtedly also second spouses, although Lutheran morality had officially put an end to polygamy.

There could be very wide age gaps between spouses, including cases of young hunters married to much older women.

- - Adoption

Adoption was a very widespread custom among the Inuit, and could be seen as a way of sharing mouths to feed within the society. Thus, orphans could survive by being integrated into a new family group. Adoption could also compensate for infertility in certain couples, providing them with material and moral support in the present and the future.

|

|

children adopted, i.e.

|

In a population of

|

|

boys

|

girls

|

total

|

|

In 1884

|

2

|

5

|

7

|

413

|

|

1892

|

6

|

9

|

15

|

294

|

|

1896

|

11

|

8

|

19

|

372

|

|

1901

|

8

|

9

|

17

|

429

|

|

1906

|

11

|

3

|

14

|

507

|

|

1911

|

10

|

2

|

12

|

550

|

Conclusion :

Various customs and survival techniques

Overall, the dynamics of this small Inuit society of seal hunters can be defined by its strong demographic vitality and great social flexibility. The latter rests on :

- * the high degree of mobility of the population (winter and summer nomadism) ;

- * remarkable flexibility in social structures : every autumn the family group would be made up differently according to the strengths available (i.e. the number and state of health of hunters present in the household during the wintering period) and to the number of people to be fed.

In the case of severe shortages, the group would allow the elderly, the sick, widows and orphans to "disappear" through "suicide", or would practice infanticide on the newborn (particularly weaklings, babies orphaned at birth through the death of the mother, and girls). Besides adoption and polygamy, examples of flexibility in the group's social organization include temporary exchanges of wives between two hunters and the possibility of raising a girl as a man or a boy as a woman [6].

[245]

REFERENCES

Bertelsen, A.

1907 Om Fadslerne i Grønland og de seksuelle forhold sammesteds. Bibliotek for laeger, 99 (8) : 527-572.

Gessain, R.

1973 Fecundity of the Ammassalimiut women (Eskimo of the East coast of Greenland). IXe Congrès International des Sciences Anthropologiques et Ethnologiques, Chicago, Aug-Sept, 4 p.

Hansen, J. (Hansêrak)

1911 List of the Inhabitants of the East Coast of Greenland made in the Autumn of 1884 ; and Notes on the List, by Holm, G. Meddelelserom Gronland, 39 (I) : 183-202.

Hansêrak

1933 see Thalbitzer, W. (ed.).

Holm, G.

1887 Ethnologisk Skizze af Angmagsalikerne. Meddelelserom Gronland, 10 (2) : 45-182.

1911 Ethnological sketch of the Angmagssalik Eskimo. The Ammassalik Eskimo : contributions to the Ethnology of the East Greenland Natives. ThalbitzerW. ed., 1914, Meddelelserom Gronland, 39 (I) : 1-147.

Krupnik, I.

1993 Arctic adaptations. Native whalers and reindeer herders of northern Eurasia, Dartmouth, University Press of New England, 355 p.

Magnusson, M.S. et J. Robert-Lamblin

1990 Approche comportementale et analyse informatique de la mobilité géographique d'une population nomade : le cas d'Ammassalik, Groenland oriental. Écologie humaine, VIII (1) : 5-23.

1994 Winter-Nomadism in the Ammassalik Region in East Greenland. Proceedings of the 9th International Congress on Circumpolar Health, Reykjavik, June 20-25, 1993, Arctic Medical Research, 53 (Suppl. 2) : 344-348.

Mauss, M. (avec la collaboration de Beuchat, H.)

1906 Essai sur les variations saisonnières des sociétés eskimos. Étude de morphologie sociale. L'Année sociologique 1904-1905, IX, Paris, Alcan : 389-477.

Mikkelsen, E.

1934 De Ostgrønlandske Eskimoer Historie. Gyldendalske Boghandel Nordisk Forlag, 202 pp.

Mobjerg, T. and J. Robert-Lamblin

1990 The settlement at Ikaasap Ittiwa, East Greenland. An ethno-archaeological investigation. Acta archaeologia, 60 : 229-262.

Rasmussen, K.

1938 Knud Rasmussen's posthumous notes on the life and doings of the East Greenlanders in olden times, H. Ostermann, ed. Meddelelserom Grønland, 109 (1) : 125 p.

Robert-Lamblin, J.

1981 "Changement de sexe" de certains enfants d'Ammassalik (Est Groenland), un rééquilibrage du sex ratio familial ? Études Inuit Studies, 5 (1) : 117-126.

1986 Ammassalik, East Greenland-end or persistance of an isolate ? Anthropological and demographical study on change. Meddelelserom Gronland. Man and Society, 10,168 p.

1997 Death in traditional East Greenland : age, causes and rituals. A contribution from anthropology to archaeology, in Klaus E, Gilberg R. and Gullev H.C. eds : Fifty Years of Arctic Research. Anthropological Studies from Greenland to Siberia. Publications of the National Museum, Ethnographical Series, Copenhagen, 18 : 261-268.

Robert-Lamblin, J. and M.S. Magnusson

1998 Film Beta SP, 23' : The Last nomads of Eastern Greenland. Editing P. Luzuy and M.-F. Deligne, Production and diffusion CNRS Audiovisuel.

Robert-Lamblin, J. et CI. Masset

1999 Démographie ancienne du Groenland oriental et perspectives archéologiques. Bulletins et Memoires de la Société d'Anthropologie de Paris, 11 (3-4) : 417-423.

Ryder, C,

1895 Beretning om den 0stgrønlandske Expedition 1891-92. Meddelelserom Gronland, 17 (7) : 147 p.

Thalbitzer,W. (ed.)

1914 The Ammassalik Eskimo : contributions to the Ethnology of the East Greenland Natives. Meddelelserom Gronland, 39,1-VI1,755 p.

1933 Den Grønlandske Kateket Hansêraks Dagbog om den Danske Konebaadsekspedition til Ammassalik i 0stgrønland 1884-1885. Det Gronlandske Selskabs Skrifter, VIII : 248 p.

Victor, P.-E. et J. Robert-Lamblin

1993 La Civilisation du Phoque. 2. Légendes, rites et croyances des Eskimo d'Ammassalik. R. Chabaud, SAI, Biarritz, 424 p.

[246]

[1] Dynamique de l’évolution humaine UPR 2147, CNRS, Paris.

[2] Infant mortality accounts for more than 30% of all deaths registered in 1897-1916 (Robert-Lamblin, 1986 : 39).

[3] According to Hedegaard (1895-1929, Archives from the Ark-tisk Institut), Holm (1887 : 56 and 162-164 ; 1911 :131-133), Thalbitzer (1914 : 346-347), Hansêrak (1933 : 73,127 and 192-193), Mikkelsen (1934 : 42-46), Rasmussen (1938 : 56-58), Victor and Robert-Lamblin (1993 : 109-146).

[4] Manuscript archives of Ryder (Rigsarkivet, Grønlands Styrelse : Ammassalik 1894-96).

[5] Like Ingemann Qinertanalik (1868-1927), Nadanieli Kuninge (1874-1955), Madsi Pusainak (1881-1935) or Samueli Mikaelsen (1897-1968), whom I met during my first field study, and for whom we determined more than 20 changes of wintering sites during an observation period of 24 years. Each Ammassalimeeq is identified by his or her personal number, gender, date of birth and death, filiations and sites where s/he wintered during the following periods : 1895-1899 ; 1901-1906 ; 1915-1930. For these periods 72 different wintering sites were coded, 62 of which were in the region of Ammassalik itself (34 at the mouth or in the interior of the Ammassalik fjord ; 18 at the mouth or the interior of the Sermilik fjord and 6 a little further south of this fjord ; 4 in the vicinity, of Sermiligaaq fjord) ; 10 were from outside the area, 5 in the north and 5 in the south. 15 000 yearly moves were recorded. The filmed representation over a map used as a background provides the best visualisation of the moves under study (cf. Magnusson and Robert-Lamblin 1990 and 1994, and the film produced in 1998).

[6] In 1884, among the 135 inhabitants of Southeast Greenland who settled permanently in the Cape Farewell in 1900, Holm had met two women hunters who owned kayaks (Hansen 1911 : 187). It should be added that the gender ratio for this group was then of 63 men for 100 women. (On this point, cf. Robert-Lamblin 1981).

|